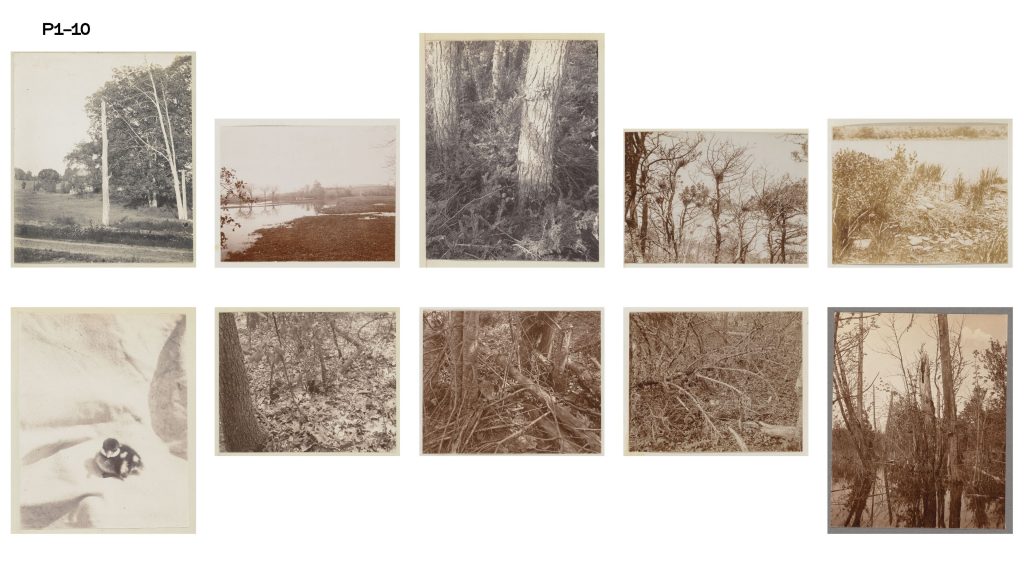

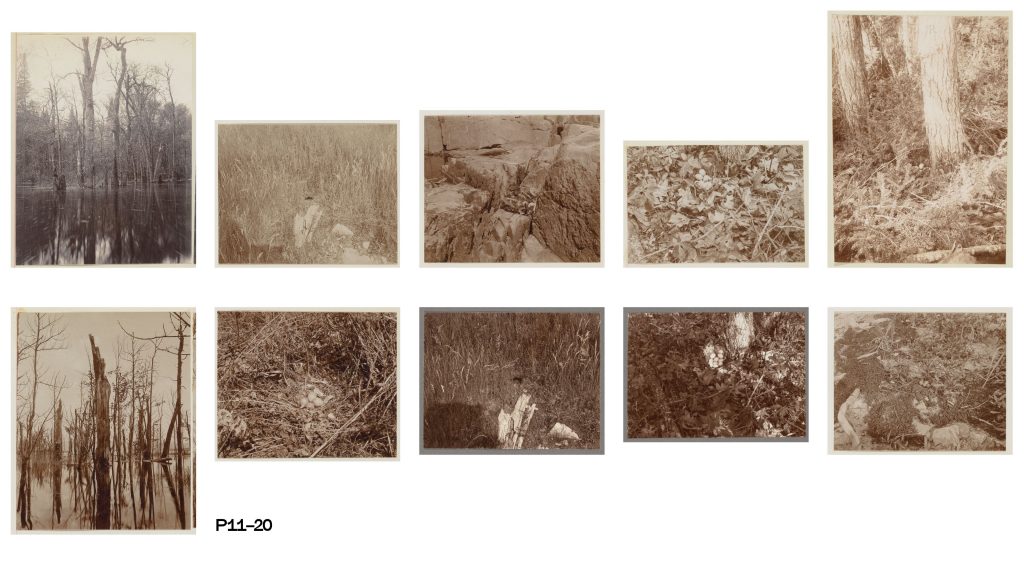

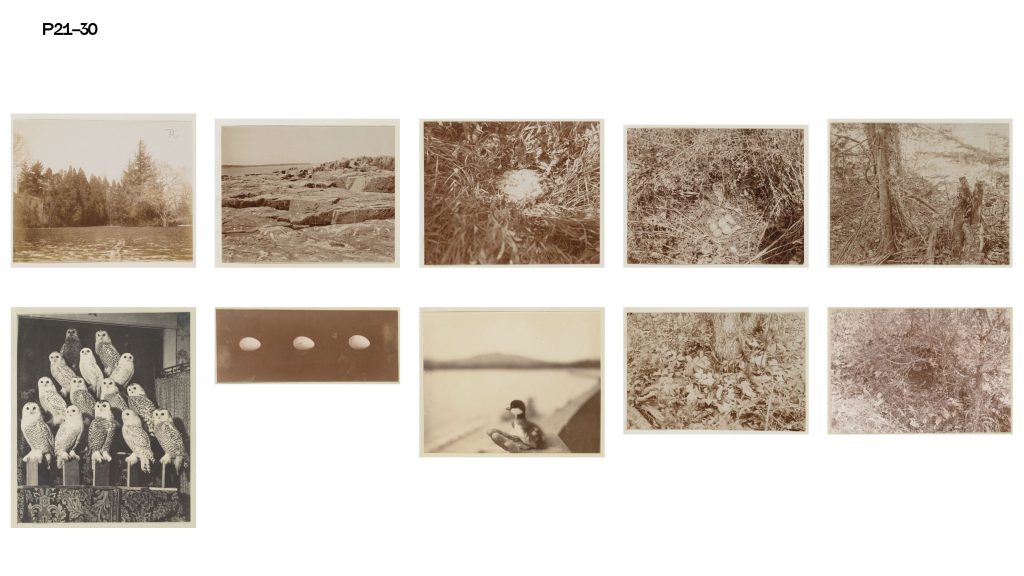

Written Response – Metadata Method

Text: Helmut Völter, The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji

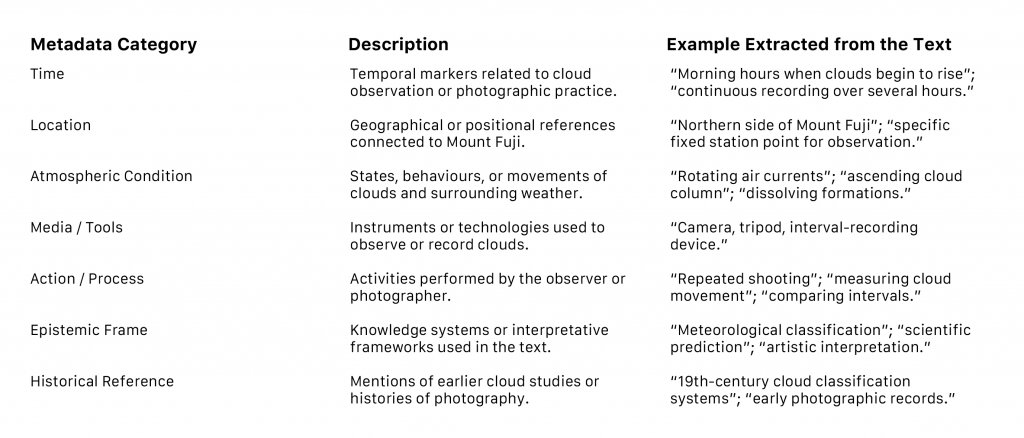

In this written response, I apply the method of metadata to analyse Helmut Völter’s The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji. Rather than summarising the narrative or the scientific content, I construct a metadata system that exposes how the text itself operates as an archive: a hybrid object positioned between meteorology, photography, and historical reconstruction. Through metadata, the reading becomes an act of reorganising the text’s informational layers, revealing structures that remain implicit in ordinary reading.

When you relabel paragraphs with metadata tags, recurring patterns emerge:

Location (fixed vantage point), Atmospheric Condition (cyclical shifts), Action (repeated photography), Time (extended duration). These tags reappear throughout the article, forming a cyclical structure. This mirrors the clouds’ behavior itself:

Clouds are cyclical, and so is the text’s narrative structure.Without metadata, this underlying structure remains largely invisible.

Metadata tags deconstruct art, science, and technology, only to reassemble them.This cataloging method imbues the text with scientific, artistic, and technical language. Metadata reveals the “rhythmic shifts” between these languages.This allows readers to recognize: Mount Fuji’s clouds are not merely a natural phenomenon, but an object shaped by the convergence of scientific history, photographic history, and visual culture.

Through metadata reading, The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji ceases to be merely a text about “clouds.” Instead, it becomes a text about how natural knowledge is constructed through tools, history, and perception. Metadata renders hidden structures, repetitive patterns, and methodological frameworks visible, offering a deeper understanding than traditional reading.

Reference:

Völter, H. (2012) The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji: Photographs by Masanao Abe.