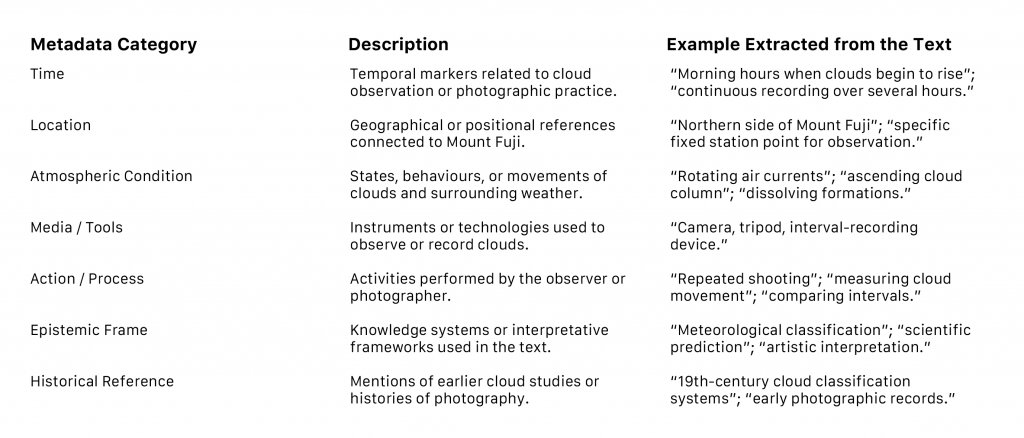

Written Response – Metadata Method

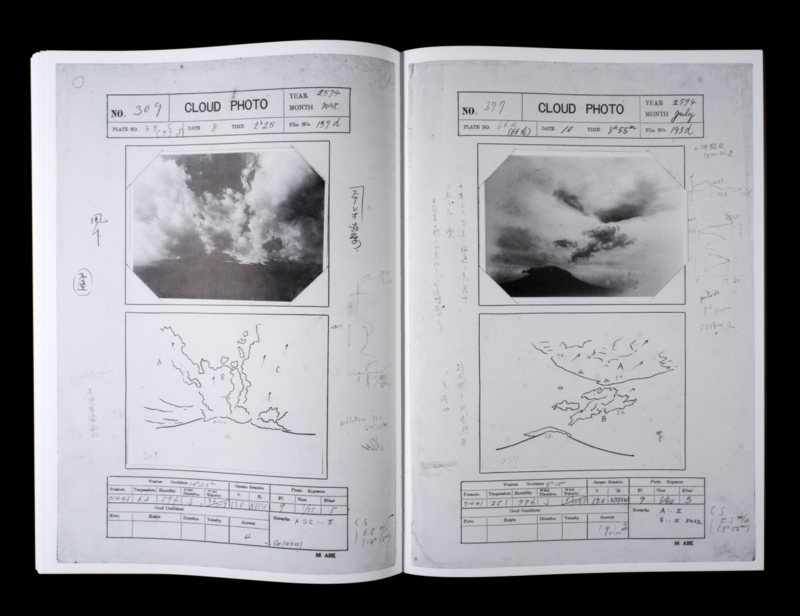

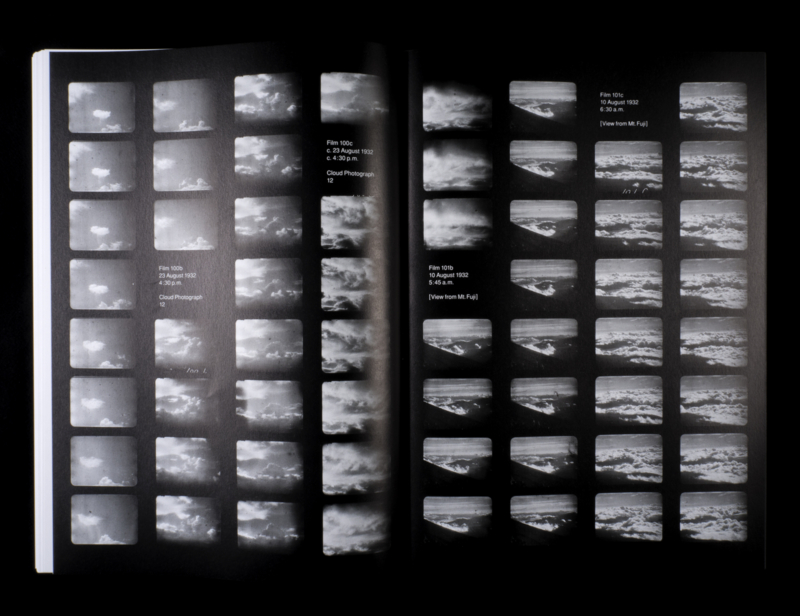

Text: Helmut Völter, The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji

In this written response, I apply the method of metadata to analyse Helmut Völter’s The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji. Rather than summarising the narrative or the scientific content, I construct a metadata system that exposes how the text itself operates as an archive: a hybrid object positioned between meteorology, photography, and historical reconstruction. Through metadata, the reading becomes an act of reorganising the text’s informational layers, revealing structures that remain implicit in ordinary reading.

When you relabel paragraphs with metadata tags, recurring patterns emerge:

Location (fixed vantage point), Atmospheric Condition (cyclical shifts), Action (repeated photography), Time (extended duration). These tags reappear throughout the article, forming a cyclical structure. This mirrors the clouds’ behavior itself:

Clouds are cyclical, and so is the text’s narrative structure.Without metadata, this underlying structure remains largely invisible.

Metadata tags deconstruct art, science, and technology, only to reassemble them.This cataloging method imbues the text with scientific, artistic, and technical language. Metadata reveals the “rhythmic shifts” between these languages.This allows readers to recognize: Mount Fuji’s clouds are not merely a natural phenomenon, but an object shaped by the convergence of scientific history, photographic history, and visual culture.

Through metadata reading, The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji ceases to be merely a text about “clouds.” Instead, it becomes a text about how natural knowledge is constructed through tools, history, and perception. Metadata renders hidden structures, repetitive patterns, and methodological frameworks visible, offering a deeper understanding than traditional reading.

Reference:

Völter, H. (2012) The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji: Photographs by Masanao Abe.

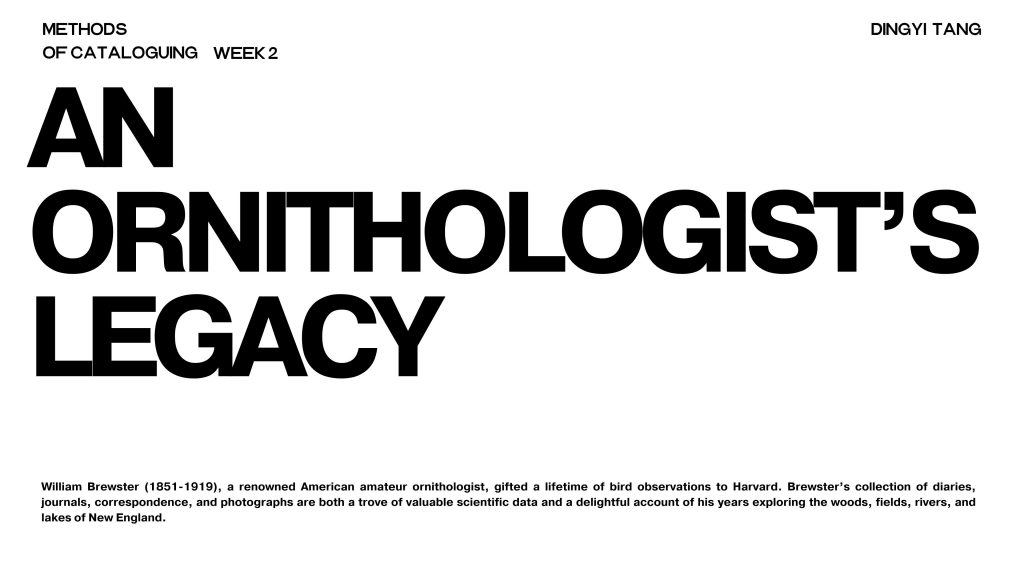

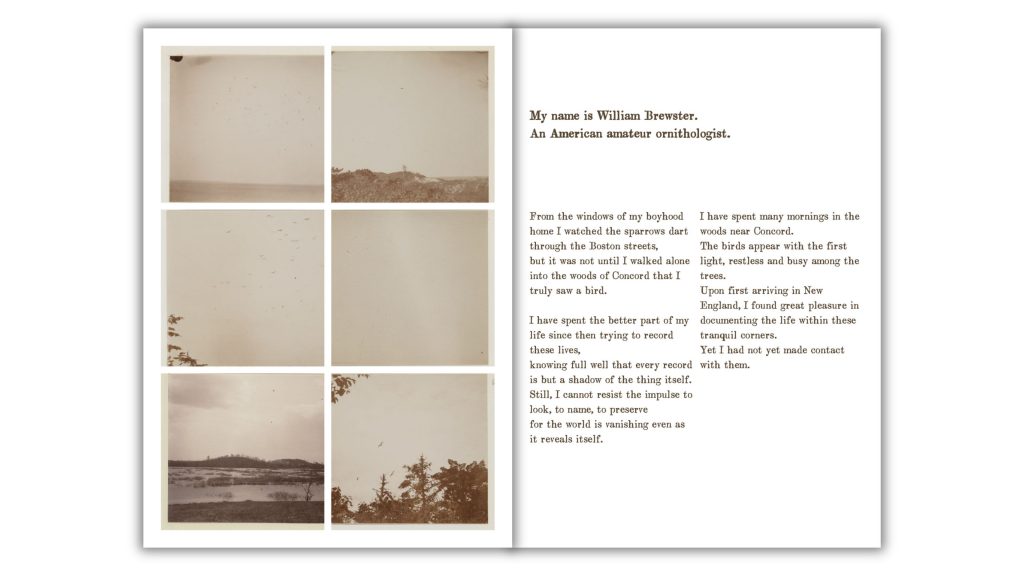

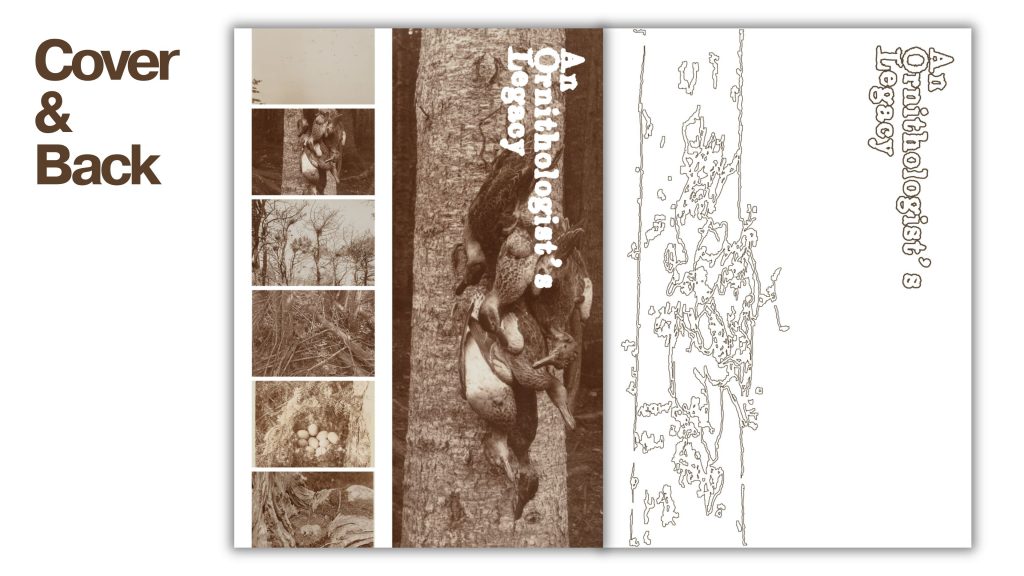

In order to present William’s record more logically and narratively,I design an archive.

A publication allows a slower reading,just like walking through memory.

I’m not creating a scientific archive book. What I’m aiming to do is to tell a story about observation.

Not just showing what Brewster saw, but reconstructing how he remembered seeing.

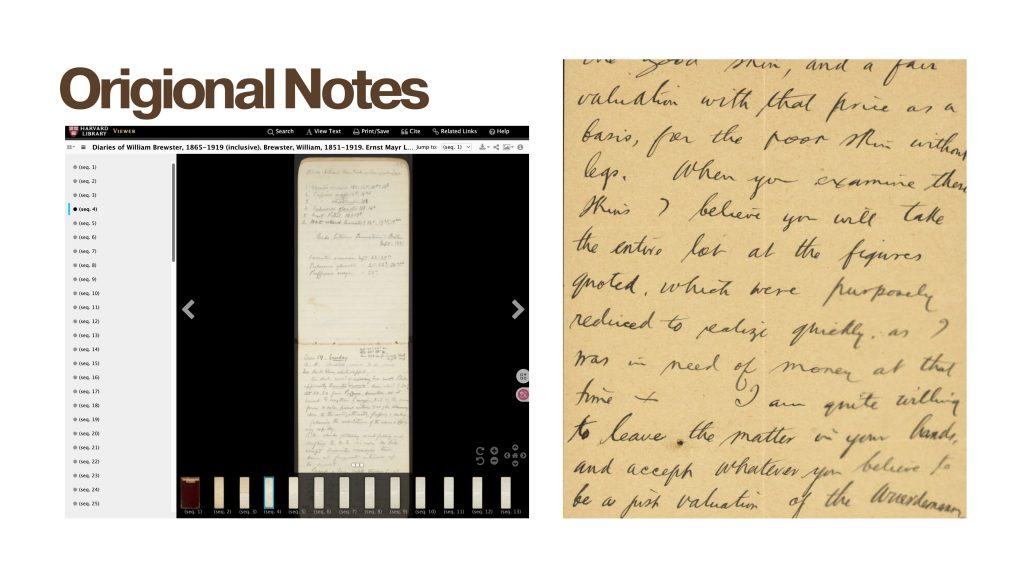

In fact, when searching for information in the Harvard archives, apart from the films he shot, I also found a large number of his diaries. This indicates that he himself was also someone who enjoyed keeping records.

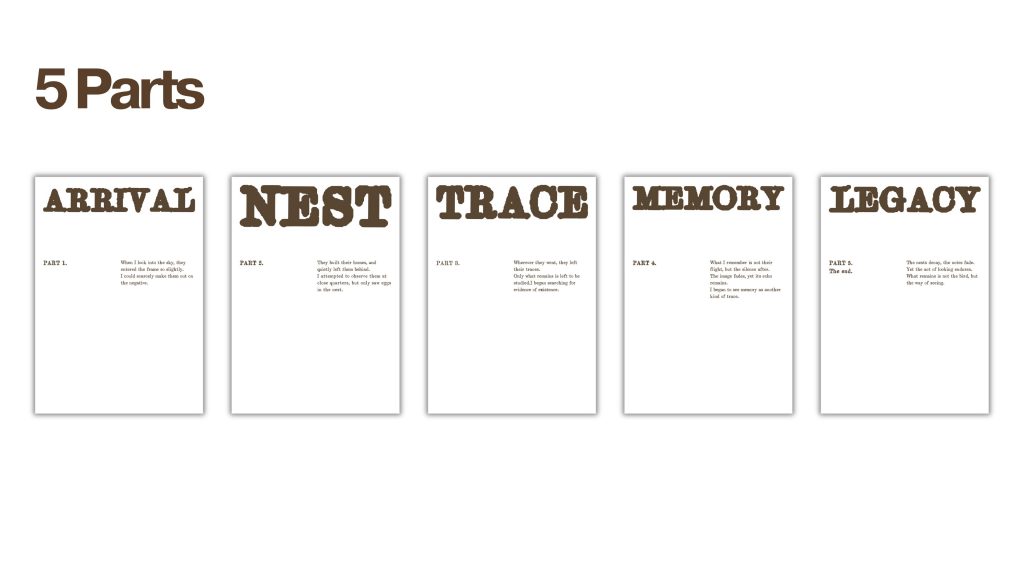

This book comprises five chapters, structured according to the timeline of the birds and William himself.

Part 1 ARRIVAL

When I look into the sky, they entered the frame so slightly.

I could scarcely make them out on the negative.

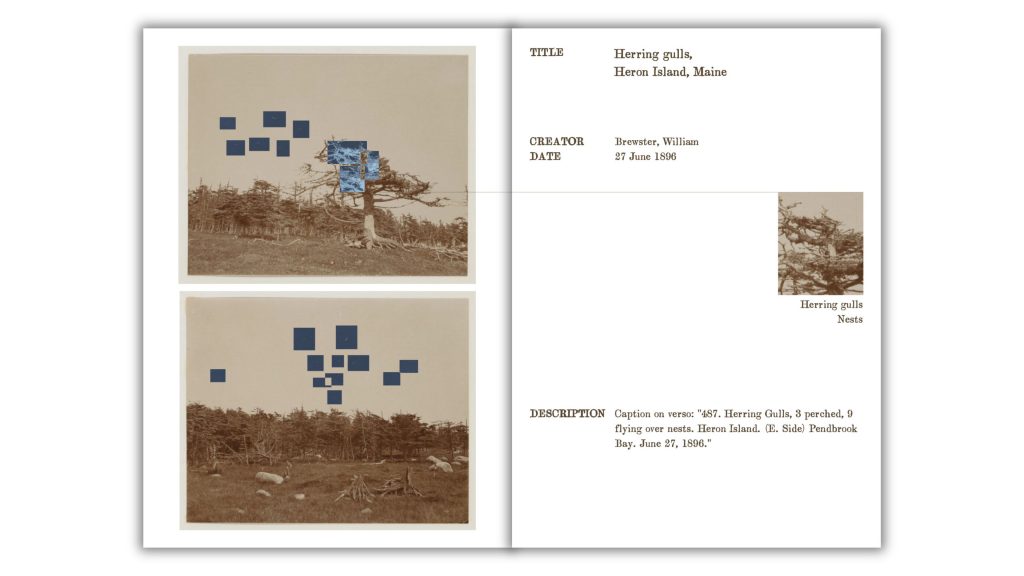

The first part is “arrival”. Here, an opening statement is also provided. This is an archive told from the first-person perspective. The “arrival” here does not merely refer to the arrival of birds, but also indicates that William began his work of observing birds around 1890. I think there is a very peculiar connection among them.

After that, I found some early photos of birds taken by William, along with their names and descriptions.

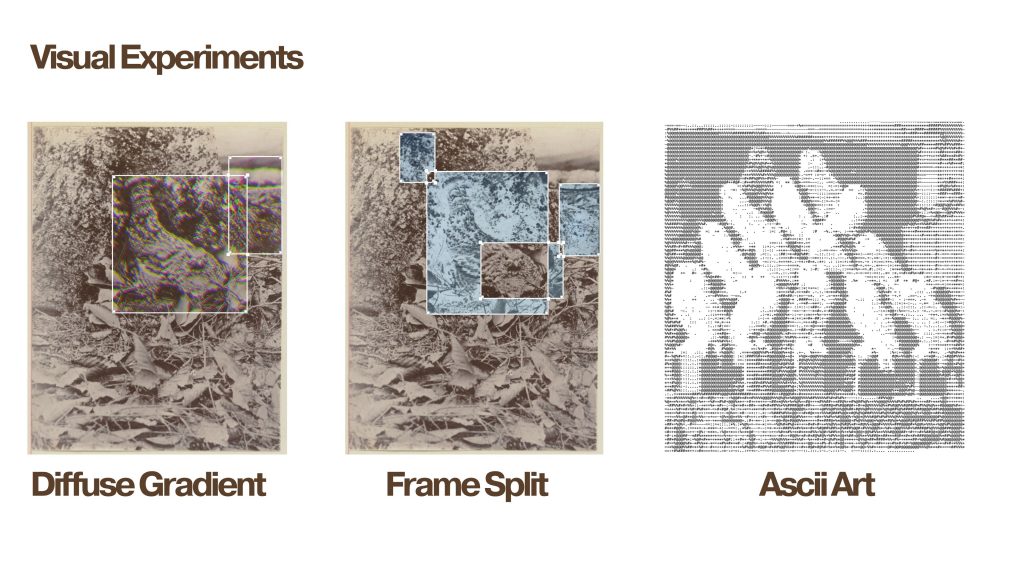

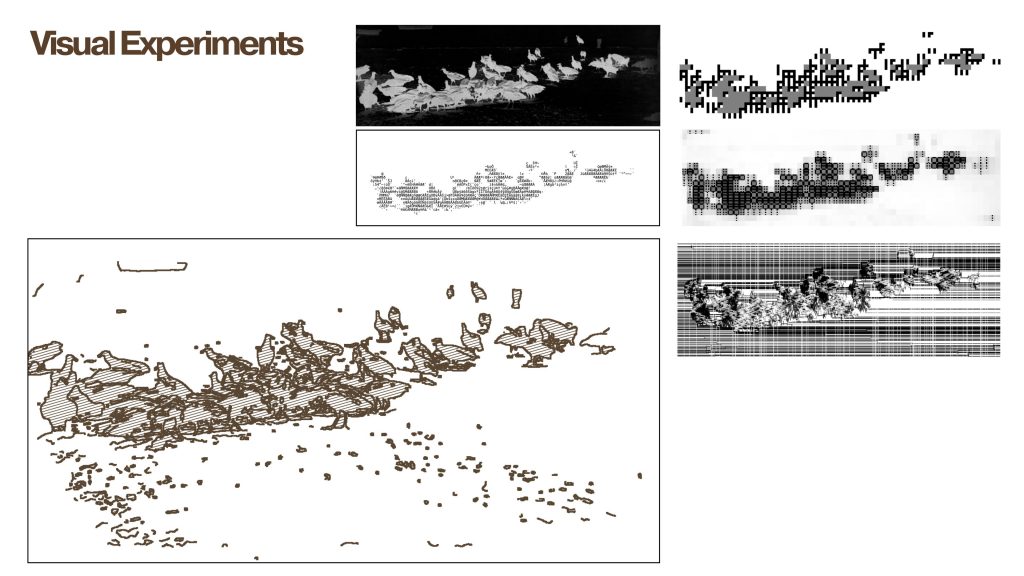

Here are some of the visual experiments I conducted. I wanted to select the birds out so that they would be easier to observe.

An interesting point is that you can observe that in the initial observations, he was always very far away from the birds.birds are very small and fuzzy.

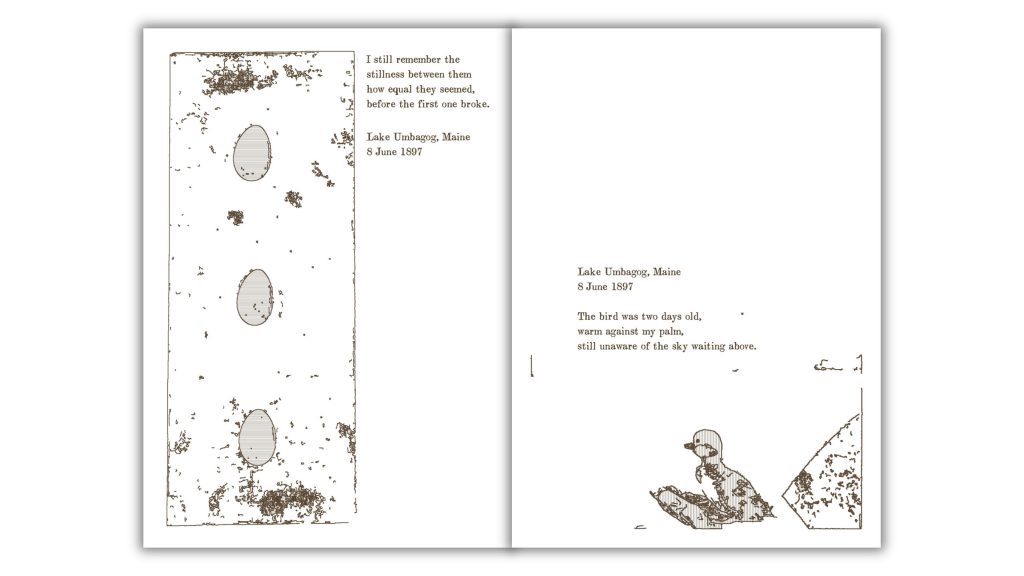

Part 2 NEST

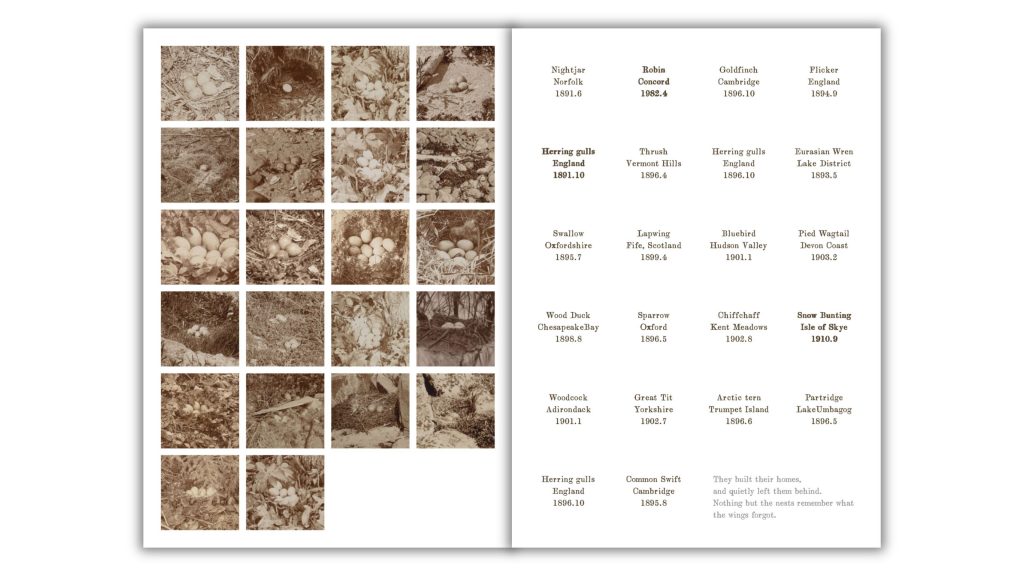

They built their homes, and quietly left them behind.

I attempted to observe them at close quarters, but only saw eggs in the nest.

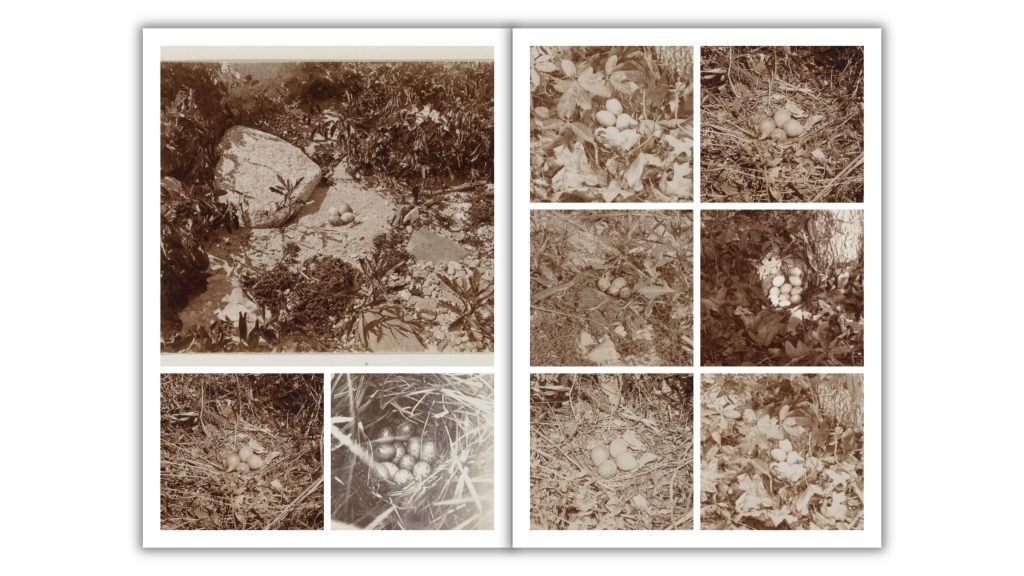

The bird’s nest might be the type of observation object that William spent the most time on.I have included the most bird’s nest photos here, along with the corresponding dates and locations.

One interesting aspect is that from this point on, the birds themselves rarely appear in their photos. This is completely different from what I imagined about a bird expert.

Part 3 TRACE

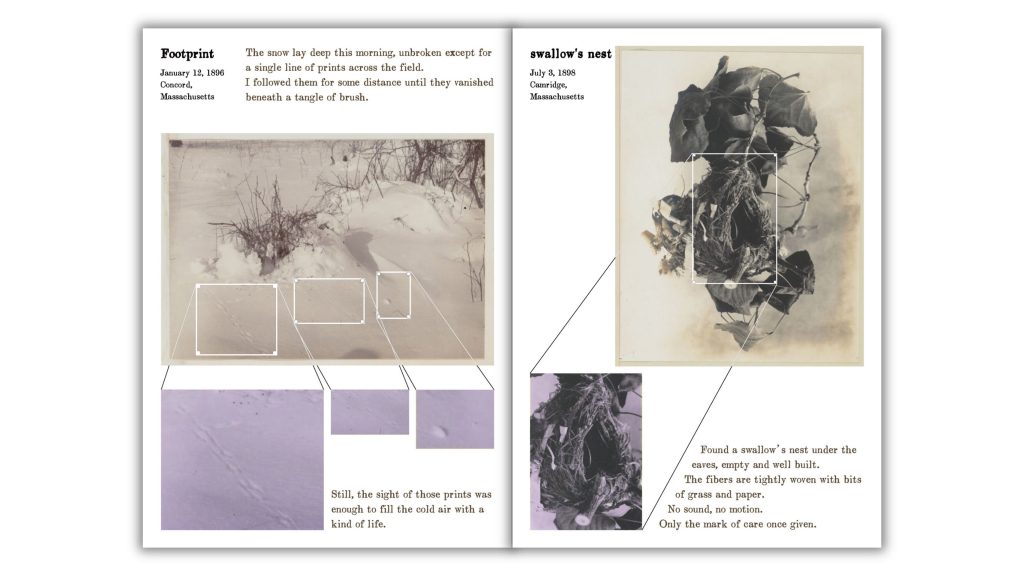

Wherever they went, they left their traces.

Only what remains is left to be studied.I began searching for evidence of existence.

Obviously, when the birds leave, they leave behind quite a few traces.Brewster’s photographs often show not birds, but traces -empty nests, footprints, tree holes.

This was a turning point. William began to search for “evidence of existence” in the absent world. He shifted from observing nature to conceptual observation.

Part 4 MEMORY

What I remember is not their flight, but the silence after.

The image fades, yet its echo remains.

The records show that when William was organizing the materials and donating them to the Harvard Library, it had been 50 years since his first observation of birds.

So in this section, I have presented the process of William’s memory loss. But I believe there are still many scenes that he will never forget.I began to see memory as another kind of trace.

This is the second part of my visual experiment. I aim to create the effect of fading and blurring memories.

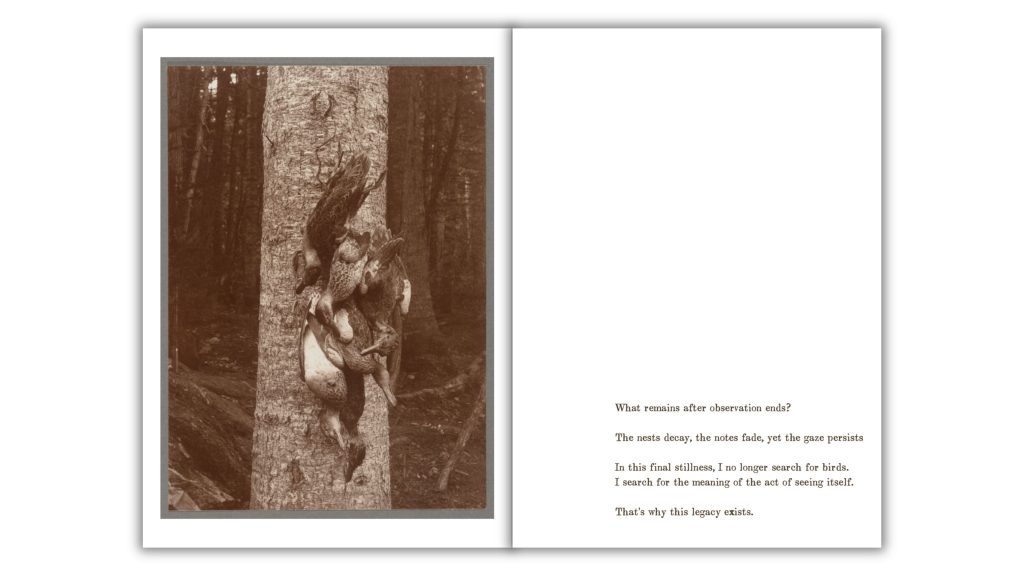

Part 5 LEGACY

This is actually just a summary.

What remains after observation ends?

The nests decay, the notes fade, yet the gaze persists

In this final stillness, I no longer search for birds.I search for the meaning of the act of seeing itself.

That’s why this legacy exists.

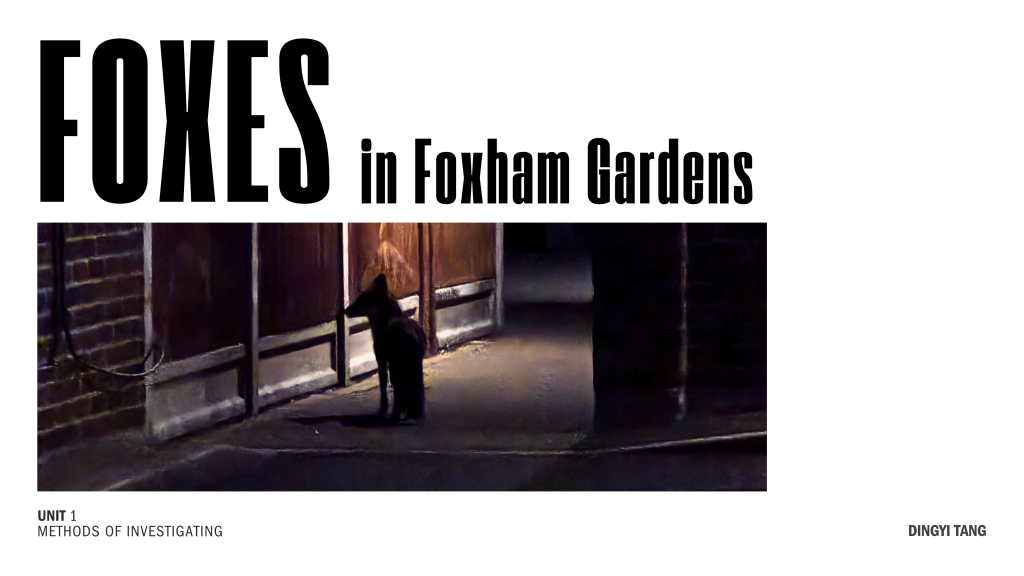

I selected the foxes in Foxham Gardens as the subjects for my research investigation.

My investigation explores how urban space can be reinterpreted through the sensory perception of a non-human species. By tracing the hidden paths, scent routes, and rhythms of foxes in Foxham Gardens, I aim to understand how alternative ways of seeing and moving might challenge human-centered lifestyles.

The final outputs comprise three components: First is the Foxham Gardens Map Guide for Foxes. Second is the data visualization: Where Can I Avoid Contact with Humans at Different Times? Third is the photographic series and documentation: If I Were a Photographer Fox.

I found two reference cases in the course. They resonated with my project through their unique interplay of observation, time, and attention.

i. In The Street, The Neighborhood, and The Town from Species of Spaces and Other Places (1974), Georges Perec invites us to look closely at what usually goes unnoticed. Through patient observation and meticulous description, he transforms the ordinary objects of daily life like cars, gestures, buildings, into realms of discovery. Perec’s perspective gradually widens from the intimate to the urban, revealing how meaning accumulates through focused attention. In my own work, I continually seek the special significance behind the commonplace objects in the garden, unfolding my imagination through the fox’s gaze. Each footprint, every rustle, every path becomes a mark of life, redefining familiar landscapes. Observation itself is both a method and a form of empathy.

ii. Masanao Abe’s The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji (1920s–1930s) represents a contrasting but complementary form of observation. One grounded in long-term patience and devotion. Over a decade, Abe photographed the motion of clouds as they drifted around Mount Fuji, producing a slow archive of atmospheric change. His repetitive recording transformed meteorology into meditation. This practice informs my own approach to mapping time and rhythm. The foxes’ movements in Foxham Gardens are equally fleeting yet cyclical, like clouds passing by. By returning to the same locations at different times to document their presence, I seek to capture these ephemeral beings that shape the rhythms of life in Foxham Gardens.

Together, Perec and Abe frame my investigation as both observational and durational. Perec’s attention to the everyday and Abe’s patience toward natural temporality guide my process of documenting the fox’s record.

References:

Bellos, D. (1999) ‘Species of Spaces and Other Pieces by Georges Perec: Translated with an introduction by John Sturrock. London & New York: Penguin Books, 1997. ISBN 014018956’, Translation Review, 57(1), pp. 41–46. doi: 10.1080/07374836.1999.10524083.

Masanao Abe, The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji Available at: https://www.spectorbooks.com/book/the-movement-of-clouds-around-mount-fuji (Accessed: 20.11.2025).

During the second week, I made a decision to change my site. However, it was only a few hundred meters away from my original location. I found the initial park too large, making my research difficult. The new site, Foxham Gardens, is smaller and more secluded. it’s also one of the parks I pass on my way home.

The first time I saw the entrance to this park, I was utterly amazed. It was completely covered in trees, with a thick layer of fallen leaves on the ground. It felt like an ecological paradise in North London.

I conducted a detailed investigation of the entrance. It was evident that the foxes were unaware of the iron gate’s purpose; they often opted for alternative entry points, such as the wider gaps between the railings.

Foxes are omnivorous animals, so they feed on both human leftovers and berries found in parks. Therefore, I attempted to survey all locations within the park where they could potentially forage.

From my observations, the foxes here are quite wary of humans, so most of the time I can only observe and record them from a distance of about 20 meters. This means they tend to prefer narrow, shady paths over wide, man-made roads.

As an outcome of this photographic observation, I created Foxham Gardens map guide tailored for different subjects.

I categorized users into cyclists, pedestrians, and foxes.

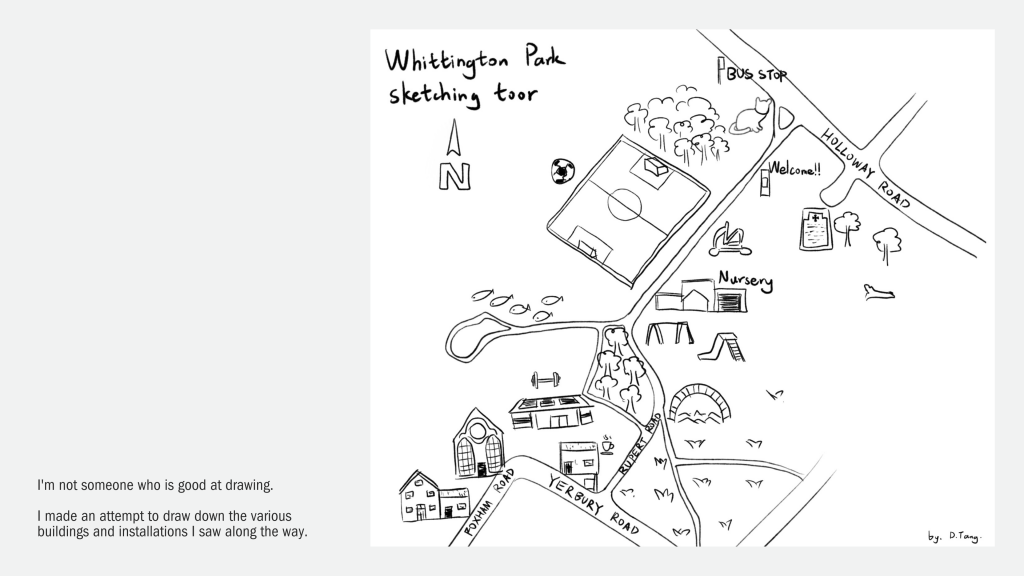

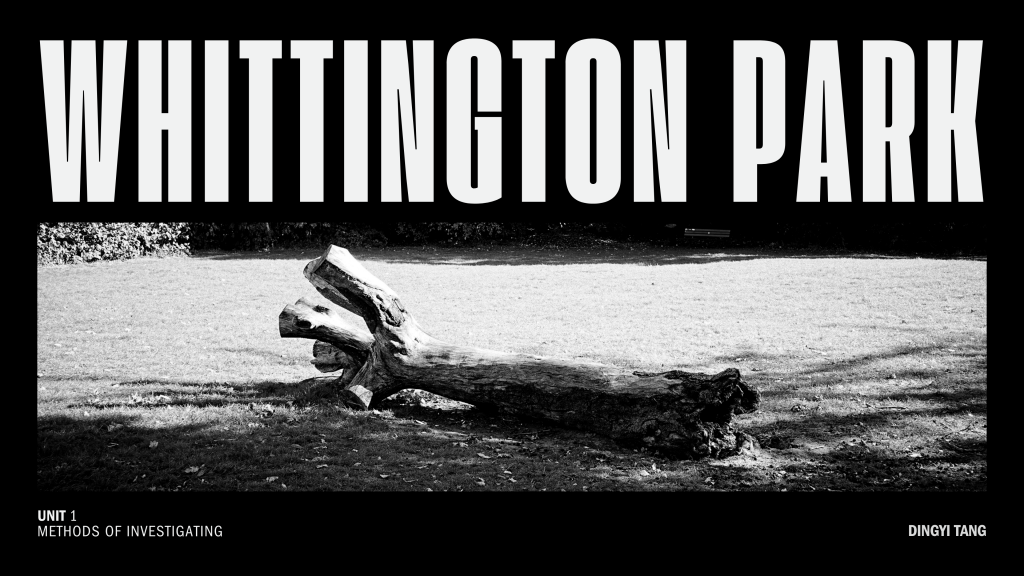

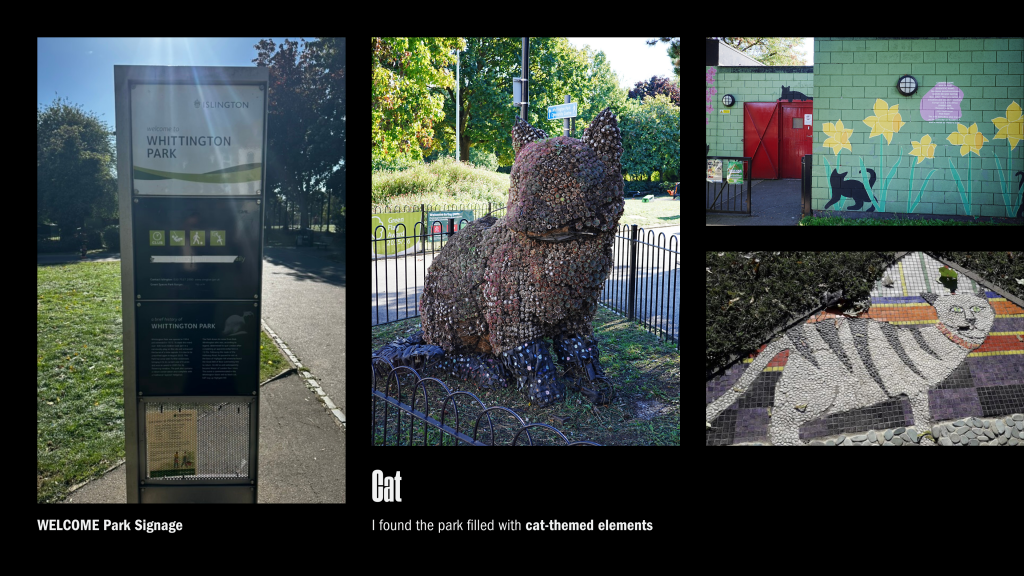

As an international student, I live near Tufnell Park in Islington. For me, every time I take public transportation to the station, I pass through several parks. Among them, Whitting Park is the largest, so I chose it as my initial site for investigation.

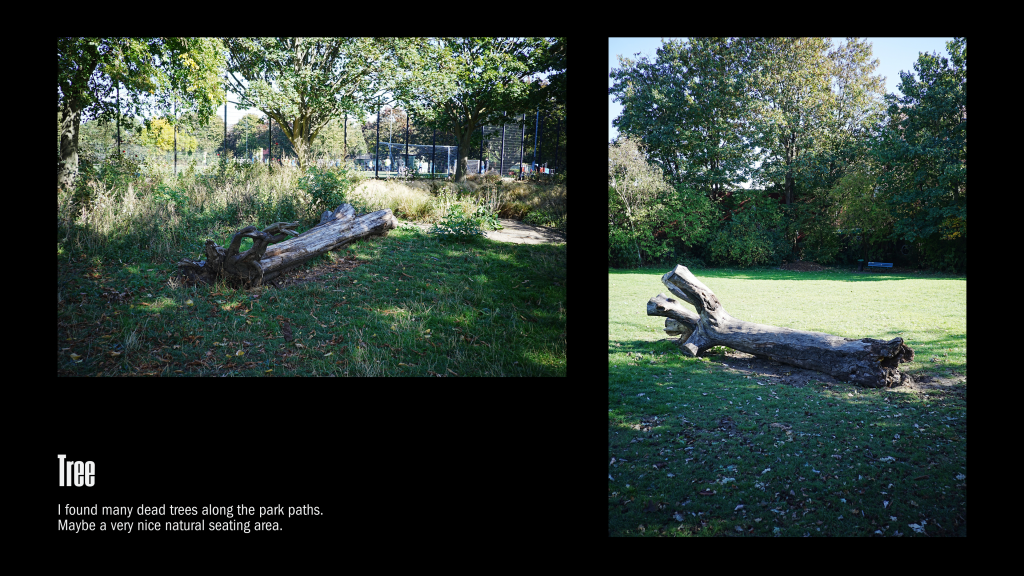

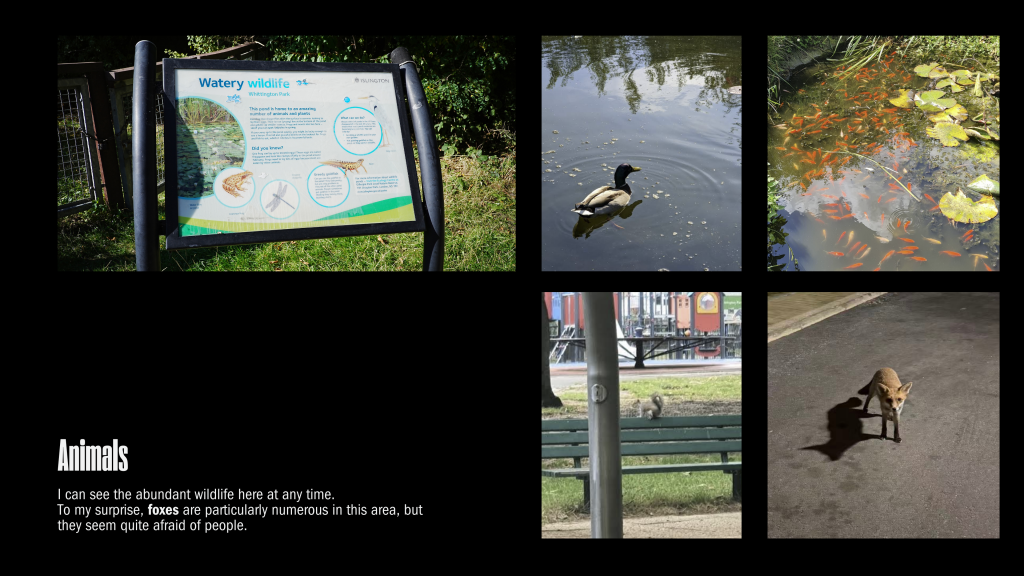

At first, I had no idea where to begin my research. As it happens, photography has always been one of my hobbies, so I picked up my camera and started snapping pictures of interesting things around the park.

Thus, photography became my first method of investigating.

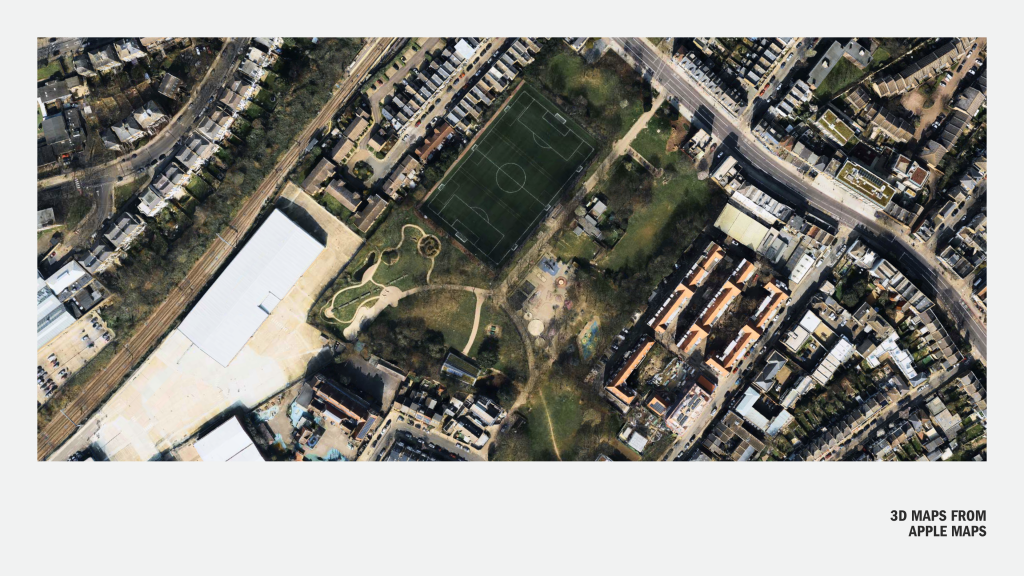

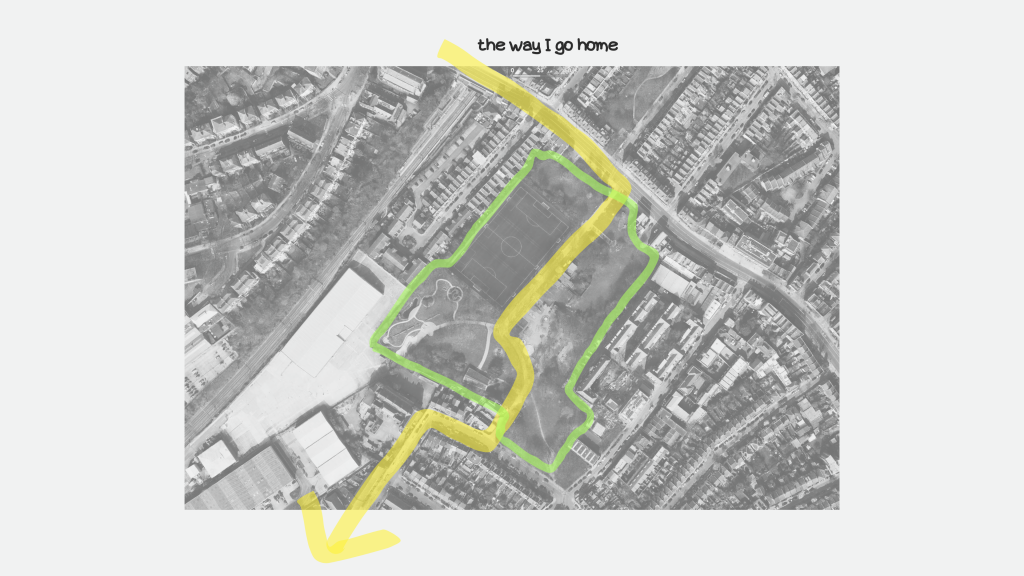

Meanwhile, since I frequent this place, I’ve also conducted mapping research. Nowadays, 3D maps of any location can be easily accessed online. I mapped out a route I often walk.

One noteworthy fact is that I frequently encounter foxes here. This has sparked my keen interest in them. Since this was a week-long project, I took the time to document how many foxes will I meet on my way home and visualized their locations on a map.

So obviously, mapping became my second method of investigating.

I have to say I’m not particularly skilled at drawing. But I wanted to challenge myself with a hand-drawn map, so I created one inspired by the vivid, hand-drawn maps from the early 20th century.

Last but not least, sketching became my final method of investigating.